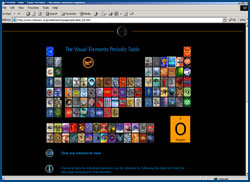

Writing style

|  Ways

of organizing and presenting scientific information continue to evolve,

as can be seen in the Royal Chemical Society's Visual Elements Periodic

Table. Ways

of organizing and presenting scientific information continue to evolve,

as can be seen in the Royal Chemical Society's Visual Elements Periodic

Table. |

The

first scientific articles are typically brief reports (seldom more than

10 pages, sometimes a single paragraph) describing an individual's

encounter with nature through observation and experiment. Particularly

in England, they tend to be a run of Baconian "facts" woven into a

narrative loosely connected, if at all, with an explanatory theory. In

general, they seek to establish credibility by means of reliable

testimony more than painstaking technical details, and by qualitative

experience more than quantitative experiment and observation in support

of theory. The early articles also largely rely on everyday language

and are written in a style conforming to the compositional norms of

expository prose generally, not norms specific to science. For the most

part, the targeted audience is a loosely knit community of amateurs and

professionals united by a curiosity about how nature works. The modern

scientific article, in contrast, has evolved a specialized language and

prose style adapted for efficient communication to other professionals

engaged in similar research. The impersonal style of these articles is

designed to focus the reader's mind on the things of the laboratory and

the natural world, rather than to draw attention to the text itself or

its author. Presentational features

The

presentational features of the scientific article have evolved in two

primary ways. First is development of a more uniform and regimented

arrangement of the article's overall content. This arrangement

represents a tribute to the efficacy of the scientific method as a

means of exploring nature. To that end, the modern scientific article

is typically divided into an introduction, which places readers in the scientific context in which its authors are working, a section on methods and materials that outlines the procedures used, a section on results that displays the data generated and the intellectual context of their acquisition, a discussion section that interprets the data and addresses future research that would extend the present insights, and a conclusion that reiterates the central argument in a single paragraph or two and brings the main body to a close.

The

scientific article has also evolved a master finding and organizing

system. This system compartmentalizes the essential features in

articles through the use of summaries and abstracts, headings and

subheadings, tables and figures integrated into the text, citations

that supply context for statements at any point in the text, and so

forth. This system permits scientists to read articles

opportunistically rather than sequentially, scanning the various

sections in search of useful bits of method, theory, and fact.

The

latter half of the twentieth century has seen a great flowering of

scientific style guides and manuals, which have codified presentational

as well as stylistic features in the scientific article and contributed

to its growing uniformity across national boundaries and disciplines. Visual displays

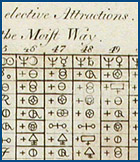

| | University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center |  Torbern Bergman's table was an early attempt to represent chemical equations. Torbern Bergman's table was an early attempt to represent chemical equations. |

At

the origin of the scientific article in 1665, several types of visual

representation had already reached maturity: tables of data had long

been a staple of the astronomical literature; three-dimensional

drawings of anatomical features had attained a high level of technical

detail and artistry, as shown by the graphics in the work of Vesalius

and Leonardo da Vinci; map making of the earth and heavens was a

long-standing enterprise; and geometric diagrams had been around since

Euclid. Moreover, illustrations of flora and fauna, as in Hooke's Micrographia,

were on a par with anything produced by graphic artists today.

Nonetheless, illustrations and tables are relatively scarce into the

nineteenth centuries, in part because of the expense involved in

reproduction. It is not uncommon to find, for example, all the

illustrations for an annual volume of a journal isolated in a slim

section at the end. The graph, invented in the late eighteenth century,

revealed the power of visualizations for conveying masses of data at a

glance and uncovering data trends. In the nineteenth and twentieth

centuries, scientists have invented many other new forms of scientific

visualization, some of them requiring highly specialized decoding

abilities on the part of the intended audience. Because of their

utility for creating and communicating science, combined with advances

in photographic reproduction and computer technology, visual

representations now play a central role in the scientific article. The languages of science

English,

French and Latin were the dominant languages of the scientific article

in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Despite the important

contributions by natural philosophers throughout Europe, the fact

remains that the work by investigators in countries like Italy, Spain,

Denmark, Russia, and Sweden, though often published in their respective

vernaculars, was usually communicated to Europe, and to the world, in

one of the three major languages of science. Moreover, the two centers

of scientific activity during this early period, England and France,

greatly preferred publication in the vernacular over Latin, reflecting

"a decisive switch from dry and bloodless scholastic erudition toward a

mixed scientific/technological literature based upon the experience of

the artisan, the practitioner, the traveler" (H. Floris Cohen, The Scientific Revolution: A Historiographical Inquiry,

1994). With the emergence of the German states as a center of

eighteenth-century research, German became a major language of science

along with English and French. In

the twentieth century, as science has become a global phenomenon,

scientific articles in Chinese, Japanese, and Russian also have become

prominent. Nonetheless, at no other time in the long history of the

scientific article has one language, what the linguist M. A. K.

Halliday aptly calls "scientific English," so dominated this genre. The

most-significant journals of science, whatever their nationality, now

publish in English. Even the French Académie des Sciences in its Comptes rendus

has turned to publishing summaries and whole articles in English. It is

no accident that, when the National Research Council of Japan launched

several new specialized journals in the 1920s, they chose English to

reach the widest possible international audience. What's next? Now,

in the 20th century, we look forward to applying electronic technology

to scientific communication. Certainly the editors and scientists who

started this whole process more than 300 years ago would be astounded

at the scope of the worldwide scientific endeavor. But I doubt that

they would have any difficulty recognizing the basically similar

characteristics of the system they started. --Eugene Garfield

Current Contents (February 25, 1980)  |  Founded in 1895, The Astrophysical Journal now publishes an electronic edition that provides articles in HTML and PDF formats. Founded in 1895, The Astrophysical Journal now publishes an electronic edition that provides articles in HTML and PDF formats. |

The

scientific article is in the midst of a radical transformation spurred

by advances in computer technology, in particular, word processing and

graphics software, electronic mail, and the World Wide Web. This

technology is changing the way in which the scientific manuscript is

prepared by authors, put through peer review, produced in final form,

distributed to interested readers, and perused by those readers. At the

research fronts of fast-moving fields like particle physics, this shift

is well on its way: scientific articles published in hardcopy

periodicals are already yesterday's news. The next century, what Steven

Harnad calls the "post-Gutenberg era," may very well witness the

extinction of the original scientific "paper" appearing on paper. And

the long-term effect of electronic preparation and publication of

manuscripts may be as profound as when the scientific article evolved

from scholarly letter writing and books in the seventeenth century. |  Nature posted the results of the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium online, free to the public. Nature posted the results of the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium online, free to the public. |

Take,

for example, the initial results of the International Human Genome

Sequencing Consortium, posted online in February 2001. For publication

of this instant classic, Nature magazine suspended its usual

practice of allowing only subscribers access to its electronic

contents, and released it to the public. We suspect this article holds

the record for the longest ever published by Nature magazine

(62 pages), where articles seldom exceed four or five pages. Its

decoding of the 3.2 billion letters in the DNA of the human genome is

the work of 20 laboratories and more than 250 scientists and computer

experts around the world. The consortium's most surprising finding

(though very tentative) was that the human genome has 30,000-40,000

protein-encoding genes--a far cry from the more than 100,000 previously

estimated. Indeed, this number is not all that much higher than less

complex forms of life like fruit flies (13,000), microscopic round

worms (19,000), and mustard weeds (26,000). This

long article ends by echoing the first sentence in the next to last

paragraph of Watson and Crick's famous DNA article from the 1953 issue

of Nature: "Finally, it is has not escaped our notice that the

more we learn about the human genome, the more there is to explore"

(italics indicate repetition of wording between the two articles). That

sentence is followed by an apt quotation from T. S. Eliot's "Four

Quartets": We shall not cease from exploration.

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started,

And know the place for the first time. |