| Summer

2002

Expedition to the Flannans

And for those of you who may

not have had the opportunity to see the web-pages leading up to the

expedition, click here to see the archived

information.

THE FLANNAN ISLES

STORY

Many will recall my August 1999

expedition to the Flannan Isles EU-118 (SCOTIA DI25), accompanied by

Keith (MM0BPP). On that occasion, we sailed overnight from

Breascleit on the west coast of the island of Lewis in the Outer

Hebrides, on the fishing boat 'Coastal Surveyor', skippered

by 'Johnnie Ronnie' MacLeod.

| This was

our first experience of the infamous Atlantic swell that, even

under calm conditions, is ever-present - surging several

meters up the near-vertical cliffs of Eilean Mòr. This is the

largest of the remote Flannan group (also known as the Seven

Hunters) and is dominated by its famous, some would say

infamous, lighthouse that stands 100 metres (almost 300 feet)

above the sea.

The Flannan Light |

|

One December night in 1900, the year

after the lighthouse was built, it was noticed the light was out. A

landing party was sent to investigate, only to discover that all

three keepers had vanished, apparently on the 15th of December (when

the last notes had been made on the lighthouse 'slate', prior to

being entered in the official log). A half-finished meal lay on the

table, two sets of oilskin clothes were missing and a chair lay

over-turned as though knocked over by someone in a rush to get

outside.

Many theories for the multiple

disappearance have been put forward, ranging from sea monsters to

aliens from outer space. A fellow island activator and hunter Donald

(GM0KCY), now retired and one of Scotland's last lighthouse keepers,

was himself a former keeper of the Flannan light. He has told me

that, in the severe weather conditions prevailing at that time of

year, waves up to 30 metres or more (100 feet) would not be

uncommon. It would not be impossible for such enormous waves to

surge up or over the rock.

The 'official' explanation of the

disappearance is based on this possibility, namely that during a

severe storm, two of the keepers perhaps went down to check

equipment or whatever, perhaps one was struck by one of these huge

waves, perhaps the other went to seek the help of the third man and

perhaps in a rescue attempt they too were swept away.

| The poem by W.W. Gibson, "Flannan Isle",

describes the impressions of those who were sent to

investigate some days later. It ends :- |

|

|

We seem'd to stand

for an endless while,

Though still no word was

said.

Three men alive on Flannan Isle

Who thought on

three men dead.

|

|

|

|

Such

events were hard to imagine almost a century later when, on a

relatively calm, summer morning in 1999, Keith and I landed on

what is referred to as the west landing - on some

semi-submerged steps leading onto a small concrete platform,

constantly washed by the swell and which, in a moment of

inattention, swept away a 5-litre fuel container (representing

our emergency allocation).

We soon discovered that a few shreds of

rusty bolts on the smooth cliff face, sloping briefly at 45°

before plunging vertically into the whirlpools below, were all

that remained of a 10-metre stretch of concrete steps

previously anchored to them. As I found out later, even the

lightest rain shower, or sea spray, or water dripping from

above would render the surface like glass, and would have made

that gap absolutely impossible to cross.

GM3VLB negotiates the steps up from the West

landing back in 1999. |

| However we had somehow edged across it and

painstakingly lugged our equipment up and along some

vertigo-inducing narrow ledges, to a second concrete platform.

This was some 4 metres square and was perched some 20 or 30

metres above the swirling sea. The platform had been the base

for a large crane that had been used to lift provisions from

the supply vessels to the base of the miniature cable railway.

This railway was then used to haul the cargo up to the

lighthouse. The raging seas had long since made a meal of the

crane and it was hardly surprising that the flimsy safety

railings were part of history too (other than two or three

very rusty stanchions between which we stretched a "safety"

rope). This platform became our base for the 4 days we spent

on the island, perched like wingless seagulls on the edge of

the cliff. It wasn't difficult to imagine the consequences of

one false step! The dome tent had to be put up without any

pegs, its guy wires being attached to whatever items of

equipment we felt might be heavy enough.

The 1999 west landing QTH with the

MM0BPP and the tent

perched on the old crane platform at

the end of the rails |

|

|

Landing from a two-metre fibreglass

dingy had been hazardous in the extreme; the operating position was

very precarious, and the condition of the sea so totally

unpredictable. It therefore came as no surprise when Johnny, our

skipper, informed us (via our handheld marine radio - an absolutely

essential item for trips like these) that the wind had veered to the

west, and to such an extent as to make any transfer from the rock's

west landing to the 'Coastal Surveyor' quite

impossible.

In practice, this meant that on our

last day, we had to make several exhausting trips up and over the

island to the so-called east landing, a long process threatened with

the ever-present possibility that the wind would veer back again!

When at last we had we were homeward bound, we vowed never to

return. Those who have had the opportunity to see our photographs

and the video footage have all agreed with those sentiments - and

the video camera's death-plunge into the sea on our last

shuttle-trip down to the east landing reminded us how easily we

might have followed it.

I would like to pause here to

re-iterate my remarks about marine-band capability. The absolute

necessity of this was hammered home when one of my fellow Scottish

island activators suffered a heart attack whilst on an expedition to

the Treshnish islands. The expedition team had marine-band

capability and were able to contact the coastguard and to receive

emergency medical advice from an on-board paramedic during the

relatively long wait for the rescue helicopter. As it happened, I

picked up the expedition's call for help on the 40m band, but

remember, there is a period at the beginning and at the end of an

expedition when there is no HF capability - and this

is precisely the time a slip can mean broken bones or worse, or when

the effort needed to carry heavy equipment up, down or even simply

across rocky landings can have disastrous consequences on even the

fittest activator.

On Scotland's west coast, there is no

guarantee whatsoever that mobile phone coverage will exist.

Sometimes, when there seemed to be no coverage, climbing to the top

of a hill has worked, but this can be unpleasant and dangerous in a

howling gale, or indeed impossible if incapacitated for whatever

reason.

Immediately after the incident

described above, I needed to replace a very aged Icom IC2E, and

decided to purchase the very reasonably priced HORA C150 handheld,

which has full transceive capability in the 2m amateur and 167 MHz

marine bands. I also had a word with a representative of the Radio

Agency who intimated that a 'blind eye would be turned' if marine

band use was limited to safety purposes. Since then, I have checked

in with the Coastguard as a matter of routine, whenever it seems

appropriate, giving details of my operation and letting them know

when I've safely left the island. I even did this recently, for what

may seem a simple trip to the Isles of Fleet (CS10).

On the more remote islands, a

marine-band radio may be the only way of communicating with the

fisherman or boatman (who often may also wish to communicate with

you). Surprisingly perhaps, although there is a telephone on St

Kilda (DI23), there are no telephones on The Monachs (DI22), the

Treshnish Isles (DI09), the Shiants (DI24), the Flannans (DI25), the

islands lying south of the Outer Hebrides or indeed many other

islands.

There are 11 GM IOTA islands (or

island groups), and I have now managed to activate all of them.

EU-008, 009, 010, 012, 092 and 123 are all easy. EU-059, 108,

111 and 112, though all relatively easy to land on, are much less

accessible and certainly more costly, except for very short "pop on,

pop off" operations where the boatman stands by for an hour or two

(thus making only one return trip). Such short operations to

relatively rare IOTA groups, leave many 'hunters' frustrated and

should in my opinion be avoided, if at all possible. On multi-island

expeditions, and even with careful planning with inter-island ferry

timetables, it is not always possible or convenient to overnight on

every island. Furthermore, operations involving overnight stays

(especially on uninhabited islands) are in an entirely different

league, as you need to be equipped (in terms of shelter, water, food

and fuel) not just for one night but perhaps for several, in the

event of bad weather. Incidentally, it is perhaps surprising, yet

critically important, to note how few islands have fresh water

available.

And finally - there is EU-118, the

Flannan Isles group, entirely in a league of their own.

| Perhaps

the passage of time plays tricks with one's memory. Almost

three years had elapsed since that first memorable visit with

Keith MM0BPP. Many had 'missed it' and many more had since

then joined the ranks of IOTA chasers. I was constantly being

asked if I had any plans to return to EU-118. At first my

reply was "not under any circumstances", before gradually

mellowing to "definitely not", then to "no plans", "no

immediate plans" and more recently to "you never know"!

The west landing (lower right) in

calm seas during the 1999 expedition |

|

I knew instinctively that I would

never again attempt a 'west' landing. If there was to

be another attempt, it had either to be (1) by helicopter or (2) by

boat at the 'east' landing (and then only in near-perfect weather

conditions). I had previously looked into option (1) and indeed did

so again. Just below the lighthouse, there is a purpose built

heli-pad used by maintenance crews from the Northern Lighthouse

Board. Apart from the fact that the cost of chartering a helicopter

is absolutely prohibitive, there are also Dangerous Goods

regulations that make it virtually impossible to transport fuel and

batteries by air. (By the way, this is also true on non-vehicular

island ferries operating between certain Scottish islands, e.g. to

the Small Isles of Muck, Rum, Eigg and Canna, where special permits

must be obtained prior to such transport). Any thoughts of 'begging

a lift' on a 'pseudo-training' exercise with the Search and Rescue

helicopter based at Stornoway in the Outer Hebrides, can also be

dismissed. They had had their 'fingers burnt' after helping an

earlier DX-pedition and were under strict orders not to repeat the

exercise.

It therefore had to be solution (2),

if at all. Knowing that Jim (GM4CHX) also needed the Island of

Scotland Award Outlier Group for his 'Activator' totals, I had

invited him to join me on a possible attempt. However, he did not

take up the offer. By this time, Alex (GM0DHZ) had also become a

seasoned island activator (with 45 islands activated to date) and so

he didn't need much coercion, even though he had seen the video of

the first expedition!!

For transport, the 'Coastal

Surveyor' was available, but try as he might, Johnny could not

find a suitable boat to transfer our equipment and ourselves from

the fishing boat. By necessity, irrespective of which landing is

used, this has to be anchored some 200m offshore. Neither he, nor I,

nor his crew, would ever consider as a candidate, the 2-metre

fibreglass dinghy originally used on our previous expedition. On

that occasion, it had twice sunk to the gunwales, both times with

Keith (MM0BPP) aboard!

|

As

the 'Coastal Surveyor' would be carrying out it's

normal fishing duties whilst we were on the rock, the boat

would have to be lifted out of the water for the duration.

There was no way it could be towed about, in the Atlantic

swell, 'behind' a working fishing boat and there was certainly

no room 'on deck'. The only other (remotely likely) candidate

would be a small 'R.I.B.' (rigid inflatable) and even then, I

had grave doubts about whether that could be hoisted out of

the sea, vertically, up by 4 metres or more depending on the

state of the tide and the severity of the

swell. |

Johnny and I reluctantly had to admit

that, with the short time by then available, another solution was

required. Alex and I were sorry not to renew our acquaintance with

the ship and its crew, which had also taken us, in July 2000, on the

long haul to St Kilda (EU-059) and back, accompanied then by my son

Niall just returned, as VP8NJS, from Antarctica and another

'weel-kent' YL activator, Lorraine (MM0BCR).

|

There are private charter

companies (as used, for example, by the Cambridge University

expedition (GB0FLA) in 1989). Such a charter would cost in the

region of $5000 nowadays. Alternatively, we could go as

individual private passengers (perhaps for $700 a head) on

such a chartered vessel but it would then be up to the skipper

to decide which islands (if any - depending on the weather!)

would be visited, or indeed whether any landing might be

possible once the boat arrived at that

island. |

|

In 1999, I had spoken about my

original Flannan plans to Murray Macleod, who runs "SEATREK", a

small commercial operation that takes fare-paying passengers on

sightseeing tours to wherever the weather allows. By 'sightseeing',

I mean whale and dolphin watching, although he also runs visits to

St. Kilda, the Flannans, The Monachs and elsewhere. I already knew

of his reputation as a first class skipper, something that is

essential to survive in those seas.

While we were on St. Kilda, that

intrepid activator Bill (G(M)4WSB) had made a lightning trip to the

Flannans himself, and with Murray's 'Seatrek' outfit.

However, it was a very short-lived operation due to a rapid

deterioration of the weather (the full force of which we ourselves

later experienced as we were leaving St Kilda). Anyone tempted to

say 'but August is summer-time' had better think again - the gales

are perhaps less severe and less prolonged than in the winter

months, but don't ever underestimate their ferocity!

I knew Murray relied on large RIBs

(over 8 metres long), and although I have ventured out in many

similar (but much smaller) RIBs on my island travels, the thought of

a 30 or 40 mile crossing, in rough seas, was a bit daunting. Despite

Bill's reassurance, hanging onto safety ropes around the perimeter

of a small RIB, with 2 or 3 metre waves crashing over you can be a

frightening, if not backbreaking experience, as Alex will readily

testify. And that was in the relatively sheltered Ulva Sound, not

more than a couple of hundred meters offshore.

As I had explained to Alex prior to

our departure, 'you pay for what you get'! Our estimate for the cost

of getting from the Hebrides to the Flannans with 'Seatrek'

would be considerably higher than we had originally allowed for, but

there was clearly no alternative. It was already the end of July,

and Murray had told me that the weather had only allowed him to

visit the Flannans twice since April, but that it looked as though

there was a possible window in the weather the first week in August.

I took the decision, chartered 'Seatrek', and summoned Alex

up from Portsmouth in the deep south of G-land.

A few days later, and a six-hour drive

from the Scottish Borders, we found ourselves at the northern tip of

the Isle of Skye. From there we enjoyed a pleasant, calm, 2-hour

crossing to the Outer Hebrides, followed by another 2-hour drive up

through the Isles of Harris and Lewis to the sheltered harbour of

the hamlet of Uigean on the island's remote west coast.

| There it

was - a brand new, beautiful, 8-metre ocean-going RIB, with

all the latest navigation, communications and safety equipment

necessary to operate in the wild waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

In fact, with his huge past experience in such vessels, Murray

had designed and built much of the open-type superstructure

himself. It was certainly a vessel that inspired

confidence.

Murray Macleod's brand new 8m RIB

"SEATREK"

with our small pile of expedition gear,

ready to go |

|

Alex and I were warmly received at

their home by his charming XYL, and a short time later Murray

himself arrived. We made final arrangements for departure the

following morning and were soon having a quick meal and stretching

out in our sleeping bags in our mini-mobile home for a well-deserved

sleep - it had been a long day, and the following one would be even

longer.

Thursday morning, on the 8th of

August, we rose early and had a light breakfast before driving down

to the pontoon where we unloaded everything required - ticking items

off against our checklist. We intended to be on the Flannans for 4

or 5 days but had emergency food, water and fuel to stretch the stay

to perhaps 10 days. When these ran out, a call to the Coastguard

would most likely ensure a return trip by helicopter (or at least an

air-drop of essential rations) and a certain mention in the various

media.

| Murray

soon arrived with a couple of family relief crew and in

minutes everything was loaded in the watertight forward

compartment. Several hundred horsepower of inboard engine

roared into life, we straddled our motorcycle type seats, cast

off, and gently purred our way through the channel leading

towards the open sea, passing the islands of Gt. Bernera

(HI27) and Vacsay (Burns Is. - HI26) to starboard, until

finally the radio masts perched on the cliffs of Gallan Head

slipped behind us on our left. Straight ahead, lying low on

the horizon, lay our objective - the dark outline of the

Flannan Isles. |

|

The radio burst into life as Murray

checked in with the Stornoway Coastguard on Channel 16, giving our

proposed itinerary and receiving the latest weather reports from

them. There was even a formal Coastguard request that Alex and I

keep in regular VHF contact with them once we were on the rock. We

then surged forward as Murray opened up to full throttle, and the

RIB rose up onto its cruising plane and settled down at something

approaching 50 mph. The earlier gentle breeze now felt much stronger

and the crests of the increasing Atlantic swell reached several

meters above the troughs.

The old story that every seventh wave

is a big one seemed to be verified. Murray never took his eye off

the sea and, every few moments, the throttles were shut back to

allow the RIB to climb carefully up and over these enormous waves.

Hitting one at full speed would surely have induced a backwards

somersault and would have spelled certain disaster. In between the

'big ones', the ride would have tested the skills of a bucking

bronco rodeo rider. I soon discovered that the jarring on the whole

human frame was slightly less if, instead of sitting, you crouched

over the seat, with your knees slightly bent to absorb the shocks

(as indeed Murray was doing at the controls).

|

As we

slowly got used to the ride, we were able to concentrate on

other things such as searching the bouncing horizon for whales

or dolphins, catching sight of the Flannan lighthouse now

visible on the skyline, or in my case trying to hold the

camcorder steady - an impossible task! After a few false

alerts, when Murray had throttled back at the shout of

"Whales!", one of our keen-sighted co-riders shouted

"Dolphins!". Sure enough, as we came to rest, wallowing in the

deep swell, a huge white dolphin crossed under the RIB with

almost lightning speed, followed by another and

another.

A white dolphin surfaces beside the

"Seatrek" en route to the

Flannans |

They shot back and forth, round and

under us, occasionally leaping in perfect synchronisation on our

starboard side that, for some reason, they seemed to prefer. We

watched these gentle giants play for a long time before gradually

turning up the throttles again. Still their huge white shapes stayed

just ahead of us, demonstrating their incredible power, speed and

agility as several metres of muscle leapt out of the water. It was

as though they knew exactly where we were headed. We thought for a

while they might lead us all the way to the Flannans but we must

have reached the outer limits of their current territory, as they

were gone as suddenly as they had arrived.

| With the

huge Flannan light towering above the near vertical cliffs of

Eilean Mòr, we were soon entering the calmer waters between it

and the other 'Seven Hunters'. There was to be only one

way on to the island. As Murray slowly edged forward, and very

briefly wedged the nose of the RIB into the rocks, I gingerly

jumped onto a narrow seaweed-covered but reasonably flat rock,

at the same time reaching for a vertical stanchion which had

been better galvanised than its neighbours. As I did this, the

swell pulled the RIB down and away below me. But, it felt good

to be on the Flannans again!

The white arrow shows the east

landing as we approach |

|

Alex followed on behind, as Murray

threw me a climbing rope and we hauled all the equipment vertically

up the face and onto the landing platform as he tried to keep the

big RIB on station in the swell. By the time I had finished, my

hands were raw (I tried to imagine the effort that would have been

required to haul a dinghy or smaller RIB from the water onto the

platform!). Murray then offered to anchor off and let the others

visit the island, but I think that they had seen how much equipment

we had and, suspecting they might be roped in as porters, they

declined the invitation!

| Alex

soon realised I had not been joking when I had spoken of

narrow concrete steps (with a depth of maybe only half a shoe

length and without any guard rail), which rose at an angle of

60° from a concrete landing stage - at this moment about 4

metres or more above sea level - that sported the remnants of

a vertical iron ladder that I wouldn't have hung my hat on.

These steps climbed to another platform some 20 metres above

the sea and, from then on, a path climbed a further 30 metres

at a 'much gentler' (!) 45° or so, but which was covered in

long, slippery grass, saturated by water running off the

higher ground. The path then met up with the 'present end' of

what remained of the mini-railway, levelling out to a slope of

about 30°, running in a long right-hand sweeping curve up to

the lighthouse.

Looking back down the steep steps

to the east landing, here we can see the 2m dingy

that was

used to do the shuttle transfer to and from the "Coastal

Surveyor" back in 1999 |

|

We began the long, multiple haul of

equipment, leaving some fuel and a car battery at the second level,

as it would not be immediately required. I had started to take my

first load up the final stretch when a massive whoosh of air

over my head made me belatedly duck. No it wasn't an RAF Tornado,

but instead was an enormous feathered bird that, though never having

seen one before, I soon identified as a skua, and more accurately

(later) as a great skua. The body length of the adult male is

typically 2 feet, with a commensurate wingspan. A great skua

attacking from behind with incredible speed and agility is not

something you ignore, and a pair of them was repeatedly attacking

me. I guessed I must be near their nesting site. They circled high

over head and each time I tried to move, they came in like fighter

bombers on the final bombing run, just skimming the ground before

climbing steeply at the last moment and missing my head by inches.

The agility of such a large bird is quite incredible. I have no

qualms about admitting that I was afraid - primarily afraid of the

possible injuries I might sustain should one of these birds'

navigation systems be slightly off-tune.

|

After

what seemed like an eternity, I had managed to edge forwards

about 50 yards and realised I was no longer a target. I was

out of their "patch". I veered off the railway track, up and

over the soggy grass, and up towards the heli-pad to select a

suitable site for the tent and the two 24-foot masts. One mast

would support the 20/40/80m multi-band dipole and the other,

the 10/12/15/17/30m version.

The QTH below the

lighthouse |

I temporarily used a brightly coloured

1-metre aluminium mast section as a 'weapon' and found this very

effective - the skua is not stupid, they were not going to be

'grounded' before me! After each attack, it took them time for them

to climb to a height high enough to launch the next dive-bombing

run, and during this time I moved forward as much as I could before

swinging round to 'repel' the next attack. It almost became a game,

a deadly one, I thought. Whether they tired, or whether they

realised I was just 'passing through' and not really a threat after

all, I cannot say, but the attacks gradually subsided and Alex

subsequently had a relatively free passage.

| Up at

the camp-site, we had no 'skua' trouble at all - throughout

our stay, and I can only suggest that the enthusiastic Sunday

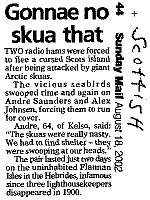

Mail reporter whose article said "Two radio hams were

forced to flee a cursed Scots (sic) island after being

attacked by giant Arctic skuas" certainly had a vivid

imagination Maybe he was reliving the scenes in Hitchcock's

film "The Birds"!

A typical 'vivid' article from the

UK tabloid press |

|

The facts of the matter were that

Stornoway Coastguard had put out a severe gale warning for Monday

the 12th of August. We could not have expected to be taken off the

rock on the Sunday, for no other reason than the long-standing local

islander's tradition of holding Sundays as their 'days of rest'. We

could have decided to ride out the storm, after all we had adequate

provisions for a few days and emergency shelter was possible in one

of the lighthouse outbuildings. However, storms in that area ARE

unpredictable, and even if it had abated, and Murray had managed to

make the trip, the big problem would still remain - the transfer

from the rock back into the RIB with all the equipment. The

Coastguard would most likely have helped in such an emergency, but

it was obvious that they would have taken a dim view if they had had

to take us off by helicopter AFTER we had ignored their weather

warning. My eventual decision to terminate the operation on the

Saturday was therefore quite an easy one.

Far from being "forced to

flee", I decided, on our second day, to venture closer to skua

territory, hopefully to induce a dive-bombing attack and capture it

on the camcorder. However, I had great trouble arousing any

interest, although one brave bird did mount a completely unexpected,

very high speed, ground level, frontal attack which took me totally

by surprise and resulted in me almost falling over backwards and

which ended up with me getting rather a poor video shot!

Radio-wise, the operation, though

curtailed, was reasonably successful. As in 1999, conditions were

poor, despite us having an apparently better site this time, being

up near the top of the rock rather than perched halfway up a cliff

face as Keith and I had been. It was primarily short skip conditions

into Europe, with virtually no early morning propagation to

W6/W7/KL7 or to VK/ZL and with only one or two JAs making it into

the log. However, despite being on the air for almost one day less

this time, my QSO total was 20% more, our overall total being around

1500. This year, we had made a conscious decision to operate not

only on more bands - indeed, I had built a second mast and another

multi-band inverted 'V' for 10, 12, 15, 17 and 30m - but also on

CW.

|

Alex

GM0DHZ found a large rock near the tent, on which he balanced

his TS-50S and his electronic keyer, with another couple of

rocks stacked to support his rear end! |

|

It was nice to hear many of our SSB

'regulars' also calling us on CW. And no, the GM3VLB/p you have been

hearing recently on CW was not a pirate! Thanks to many torture

sessions organised by well-known Dxer Steve Gibbs (GU3MBS/VQ8CC

etc.etc.) back in 5Z4-land in the 60s, I am still occasionally

capable of a respectable performance on the key!

| We had

pitched our tent on the only bit of flat ground available,

immediately next to the heli-pad. It would have been

interesting to see if it would have survived the down-draught

of a helicopter landing! Certainly, we would have had to lower

our HF multi-band dipole had we had such a visitor.

The Flannan Lighthouse

helipad,

with the QTH in the background |

|

During one of our few breaks, other

than those for hurried meals, we were able to explore a bit. Extreme

care must be taken on the rock - any slip could prove fatal. One

strange fact is that although we were visiting at the same time of

year, we did not see any sign of the hundreds of black rabbits I had

seen with Keith in 1999 - not a single one - where they have gone, I

do not know.

I talked Alex into going down to the

west landing, and to the cliff-side perch where Keith and I had

'pitched' the tent in 1999. We discovered that there had apparently

been a major rock-fall, and several metres of the track just above

the tiny platform were now missing, presumed to be in the sea. In

fact, there seemed to be a more pronounced slope on the platform

itself, and I would not be at all surprised to find the whole of

this gone before too long. I suspect that water from above is

gradually eroding the underside surfaces of the concrete and the

iron and steel used to reinforce and/or anchor it. I would certainly

NOT consider camping on it now!

There was an eerie silence at night -

with little wind, there was just the sound of the sea surging up and

down the cliffs The ghosts of the missing lighthouse keepers seem to

be the quiet type! The beam from the light, seen a considerable

distance out to sea, was sweeping rhythmically over our heads but,

in the clear air above, it was invisible to us. The light is powered

by a large array of solar panels and we noticed that the huge

mirrors rotate not only at night, but throughout the day as well

(when the light itself is of course extinguished). Presumably, once

moving in their bed of mercury, it takes less energy to keep them

moving than it would to start and stop them each day. The lighthouse

is well maintained, by the Northern Lighthouse Board. On my first

visit, the maintenance crews had just finished their stint on the

rock, and it was disappointing to see so much discarded rubbish

lying around in corners that were sheltered from the near

ever-present wind. What kind of people would leave empty beer cans,

cigarette packets, broken bottles etc., lying in such quantities in

such a remote and otherwise unspoilt environment. I had reported

this on my return and it was therefore a pleasure to see that a

cleaning party had largely removed this human detritus. (Sadly, I

see more and more of this sort of pollution on my island travels.

Some of course is washed up on shores, sometimes well above the high

tide mark by high seas, but too often, it is the result of

inconsiderate visitors who presumably behave as they would on their

home patch).

All too soon (and only because of the

severe weather warning), it was time to dismantle and make the

multi-trip journey down to the east landing to wait for Murray. It

seemed incongruous that we should be doing this in near perfect

conditions (but three days later we were forcibly reminded that

Hebridean weather can be very fickle, especially around these more

remote and exposed islands. Direct radio contact with Murray and

'Seatrek' had not been possible whilst we were on the rock,

as its homeport of Uigean lies sheltered below some west facing high

ground. Fellow activator Peter GM3OFT had been our principal

mainland 'back-up' and he was in touch with my XYL Veronica (who

relayed news on to Alex's XYL, Susan) Also keeping in touch with

Murray was my son Niall, in Aberdeen, who had found that he and

Murray shared a common passion for (ancient?) Landrovers!

We had also maintained regular

contact, via the marine band, with Johnny on the 'Coastal

Surveyor' - never far from the Flannans, as he took advantage of

the better weather to pick up a few crabs and lobster from the rich

waters around the islands. We had also monitored Stornoway

Coastguard's regular weather bulletins for our area and had

reassured them directly, from time to time, that all was

well.

As we brought down the last of the

gear, I called "Seatrek" and Murray's reply was soon followed

by Alex's superior eyesight detecting a fast-moving speck on the

horizon. The RIB was soon alongside. It was a really fine afternoon,

and some of the family had come along for the trip. While two

climbed up to the lighthouse, some of the younger generation did a

spot of fishing as everything was reloaded and stowed safely

away.

|

Eventually, passengers and equipment were back on

board and the Flannans were soon becoming a diminishing speck

on the horizon. As I looked back, I wondered when they might

next be activated. Just as mountaineers answer "because

they're there" when asked why they risk life and limb

in dangerous climbing exploits, so it will always be with

islands, whether they are on the IOTA list, or the SCOTIA or

whatever.

GM3VLB on his second expedition to

the

Flannans - will there be a third

visit? |

There are certainly far more difficult

and dangerous islands to land on and activate than Eilean Mòr in the

Flannans. I believe for example, that as long as the island of

Rockall remains on ANY island list, someone will, sooner

rather than later, attempt an operation. I only hope they live to

tell the tale. I believe that former SAS man Tom Maclean did land

(in the 1980s?) and did make some amateur radio QSOs but as he did

not have a proper licence, they were invalid. I had personally

researched the situation in the early 70s (with the help of Royal

Navy contacts as a helicopter landing would have, without question,

been necessary) and again in June 1997 when a former physics pupil

of mine was himself on Rockall as part of a Greenpeace protest team.

He approached the Greenpeace top brass on my behalf but the latter

were understandably reluctant to take on an extra

'liability'.

| Now, at

the end of 2002, within months of collecting the state

pension, I have given up any, even remotely held, ambition to

activate Rockall (did I hear someone say they had a

helicopter?!!). As they say, that's for the birds (and

madmen!).

The 'island' of Rockall, shown

here with

waves crashing over its summit |

|

| That

night, Alex and I enjoyed hot showers, a good meal, pleasant

international company and a comfortable bunk in the Garenin

Scottish Youth Hostel, on the northwest coast of Lewis. We had

often stayed there before and, recognising us, the warden

welcomed us once again. We relaxed for a couple of days and

took the opportunity to visit Johnny and his good lady Annie

and her delightful mother.

The communal kitchen at the

Garenin Scottish Youth Hostel |

|

It was Saturday and the 'Coastal

Surveyor' had also returned to unload its catch, the Sabbath

still being a day of rest for many in those parts, and when anything

smacking of work is very much frowned upon. I had promised to try

and set up a two-way marine link between Johnny's house and the

'Coastal Surveyor'. The change from an analogue to a digital

mobile-phone system in the Outer Hebrides had meant the loss of a

vital communications link, as the range was now too great for mobile

telephone communication. Johnny normally fishes around the Flannans

and beyond, and is often away for 6 days at a stretch. It is

understandable that, with no news, one or other could become

anxious, especially in times of severe winter weather conditions. I

understand that Stornoway Coastguard is very helpful in such

situations, but relayed messages are always somewhat

limiting.

I had my MFJ-259 antenna analyser with

me, and we were able to erect and test a marine-band antenna at

their home. We also set up a power supply and checked that the

installation on the boat was in good order, despite the severe

environment it is regularly subjected to. On the Monday, the fishing

boat was once again 'working the Flannans' and we were all

delighted, especially Annie, to hear 59+ signals both ways. It is

nice to be able to help such friendly people, and to repay the

kindness and hospitality that we so often encounter in the

islands.

|

Later

that day, and that night, we were on Great Bernera (HI27), and

the weather began to turn nasty - as had been predicted by the

Stornoway Coastguard. The following day, Alex was able to

activate Lewis and Harris (HI21) before we set up camp on what

looked like a disused military site high up on the Island of

Scalpay (HI19), overlooking its lighthouse, and looking out

towards the Shiants Islands (DI24) where I had been a guest on

Peter (GM3OFT)'s expedition less than a year previously (again

in horrendous weather conditions!).

The mobile QTH on Gt Bernera

Scalpay lighthouse with the

Shiants in the background |

|

| The next

day, there seemed to be a lull as we sailed back to the island

of Skye (CN14). But this didn't last long. In fact, by the

time we passed through Portree, the main town, it was

deteriorating into a wild night. We had held the faint hope

that we might make the last ferry of the day from Sconser, on

Skye, crossing over to Raasay island (CN24). The ferry from

the Hebrides had been late arriving in Skye, and I was

'pressing on' trying to get there in time.

The Cuillins on Skye, seen in the

background,

from the QTH on Raasay |

|

Although I had been having

increasingly difficulty steering the car, it was only when I nearly

didn't get round a fairly tight bend and the rear end slipped a bit

on the flooded roads, that I pulled in to a lay-by and discovered an

absolutely flat rear tyre! Of course, where was the spare?

Naturally, it was in its recess in the floor of the boot, UNDER all

the gear - and of course all I had was the original manufacturer's

jack (with its mechanical advantage geared to the needs of the

average 90-year-old lady when changing a wheel). We still beat all

records however, literally throwing everything out of, and

eventually back into, the boot, and eventually arrived at the

Sconser slipway - now firmly expecting to be camping there overnight

- only to find I had misread the time-table and we had fully 15

minutes to spare! In fact we had even more than that, as we could

now see the approaching ferry making slow headway in very heavy

seas.

The Raasay crossing is fortunately

quite a short one (which was to be even more exciting the following

morning as we returned to mainland Skye). It was a wild, wild night

but we had managed to park in what seemed like a small, almost

flooded quarry, which gave us shelter on three sides. By good

fortune, the fourth side was open with a clear take-off over the sea

crashing ashore a few hundred meters down the slope from us. The car

once again became our shack, and restaurant, and hotel, all rolled

into one. We have become quite proficient at this now and it means

we can be on the air almost immediately, using a variety of aerials,

including a full quarter-wave on 20m, whenever the car is available

to us. Indeed all our operations on this trip, other than

from the Flannans, were made using vehicle-mounted

antennae.

The following morning we watched in

amazement as the small ferry that was to take back to mainland Skye,

was wallowing in and being battered by extremely high seas. We

boarded it in trepidation, but arrived a short time later, none the

worse, on Skye. A short drive soon saw us activating Skye from the

end of the pier at Broadford, over-looking Broadford Bay ahead and

to our right, and the island of Pabay (CN17) to our left. I was

going to say we had water on three sides, but in reality it was

actually four sides, the fourth being the roof! Though the sea was

several metres below the level of the pier, huge waves were almost

totally submerging us every few moments. The car was being severely

buffeted on its right-hand side by almost continuous gusts of wind,

which must have been reaching well over 100kph.

Although fully loaded, I was still

somewhat concerned and in fact reversed the car back two or three

metres such that a large, substantial, lamp-post on our left-hand

side would hopefully act as a safety barrier should the 'big one'

hit us. It was almost hurricane conditions and we were glad when

time dictated that we should head for home, once again paying the

extortionate toll (£5.70 each way) to cross the relatively short

Skye Bridge. (I am quite sure such a level of toll in a very rural

area, with a fragile economy, would never be accepted south of the

border. As I recall, even the massive Dartford Bridge over the

Thames in London only costs £1. I would be failing the people of

that region if I didn't add my voice in protest at this

government-backed extortion - by both this and the previous

governments).

The weather improved slightly, and

some 6 hours later we were back in the Borders, 'ready for the next

one'. Since then of course, we have completed an 11-island

expedition to the Shetland, EU-012, and one to the Isles of Fleet

(CS10) but that is another story, for another time!

73 de André

(GM3VLB) |